ââ⢠All Art Is Portrait of Patron Religious Icon or Religious Celebration

A donor portrait or votive portrait is a portrait in a larger painting or other work showing the person who commissioned and paid for the image, or a member of his, or (much more rarely) her, family. Donor portrait normally refers to the portrait or portraits of donors alone, as a section of a larger work, whereas votive portrait may often refer to a whole work of fine art intended every bit an ex-voto, including for example a Madonna, specially if the donor is very prominent. The terms are non used very consistently by art historians, as Angela Marisol Roberts points out,[one] and may also exist used for smaller religious subjects that were probably made to be retained by the commissioner rather than donated to a church.

Donor portraits are very common in religious works of art, specially paintings, of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, the donor commonly shown kneeling to ane side, in the foreground of the image. Often, fifty-fifty tardily into the Renaissance, the donor portraits, especially when of a whole family, will exist at a much smaller scale than the principal figures, in defiance of linear perspective. By the mid-15th century donors began to be shown integrated into the chief scene, as bystanders and even participants.

Placement [edit]

Male side panel of Hans Memling's Triptych of Wilhelm Moreel; the father is supported by his patron saint, with his 5 sons backside him. The central panel is here.

The purpose of donor portraits was to memorialize the donor and his family, and particularly to solicit prayers for them after their death.[2] Gifts to the church of buildings, altarpieces, or large areas of stained glass were often accompanied by a bequest or condition that masses for the donor be said in perpetuity, and portraits of the persons concerned were idea to encourage prayers on their behalf during these, and at other times. Displaying portraits in a public identify was likewise an expression of social condition; donor portraits overlapped with tomb monuments in churches, the other principal way of achieving these ends, although donor portraits had the advantage that the donor could meet them displayed in his own lifetime.

Female side of Memling's Triptych of Wilhelm Moreel, the mother, Barbara Van Hertsvelde is supported past her patron saint, with her xi daughters behind her.[3] The central panel is here.

Furthermore, donor portraits in Early Netherlandish painting propose that their additional purpose was to serve as role models for the praying beholder during his own emotional meditation and prayer – not in lodge to exist imitated every bit platonic persons like the painted Saints just to serve as a mirror for the recipient to reverberate on himself and his sinful condition, ideally leading him to a knowledge of himself and God.[4] To do so during prayer is in accordance with late medieval concepts of prayer, fully developed by the Mod Devotion. This process may be intensified if the praying beholder is the donor himself.[5]

When a whole building was financed, a sculpture of the patron might be included on the facade or elsewhere in the building. Jan van Eyck's Rolin Madonna is a pocket-size painting where the donor Nicolas Rolin shares the painting infinite equally with the Madonna and Child, but Rolin had given keen sums to his parish church building, where it was hung, which is represented by the church above his praying easily in the townscape behind him.[6]

Sometimes, as in the Ghent Altarpiece, the donors were shown on the closed view of an altarpiece with movable wings, or on both the side panels, every bit in the Portinari Altarpiece and the Memlings higher up, or just on one side, as in the Mérode Altarpiece. If they are on different sides, the males are ordinarily on the left for the viewer, the honorific right-hand placement within the movie space. In family groups the figures are usually divided by gender. Groups of members of confraternities, sometimes with their wives, are besides found.[7] Additional family members, from births or marriages, might exist added after, and deaths might exist recorded by the addition of small-scale crosses held in the clasped hands.[eight]

At to the lowest degree in Northern Italia, as well as the grand altarpieces and frescos by leading masters that attract well-nigh art-historical attending, there was a more than numerous group of modest frescoes with a unmarried saint and donor on side-walls, that were liable to be re-painted as presently as the number of candles lit earlier them barbarous off, or a wealthy donor needed the space for a big fresco-bicycle, as portrayed in a 15th-century tale from Italian republic:[9]

And going around with the chief bricklayer, examining which figures to go out and which to destroy, the priest spotted a Saint Anthony and said: 'Save this one.' And so he found a figure of Saint Sano and said: 'This i is to exist gotten rid of, since equally long every bit I accept been the Priest here I accept never seen anyone light a candle in front of it, nor has it ever seemed to me useful; therefore, stonemason, become rid of it.'

History [edit]

13th-century frescoes from Milan: Madonna and Child, Saint Ambrose, and the donor Bonamico Taverna)

Donor portraits have a continuous history from tardily artifact, and the portrait in the sixth-century manuscript the Vienna Dioscurides may well reflect a long-established classical tradition, just as the author portraits found in the aforementioned manuscript are believed to do. A painting in the Catacombs of Commodilla of 528 shows a throned Virgin and Kid flanked by two saints, with Turtura, a female person donor, in front of the left hand saint, who has his mitt on her shoulder; very similar compositions were being produced a millennium later.[10] Some other tradition which had pre-Christian precedent was royal or royal images showing the ruler with a religious figure, normally Christ or the Virgin Mary in Christian examples, with the divine and royal figures shown communicating with each other in some way. Although none have survived, there is literary bear witness of donor portraits in small chapels from the Early Christian period,[11] probably continuing the traditions of pagan temples.

The 6th-century mosaic panels in the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna of the Emperor Justinian I and Empress Theodora with courtiers are not of the type showing the ruler receiving divine blessing, but each show 1 of the regal couple continuing confidently with a group of attendants, looking out at the viewer. Their scale and composition are alone among large-calibration survivals. Likewise in Ravenna, there is a small mosaic of Justinian, peradventure originally of Theoderic the Great in the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo. In the Early Middle Ages, a grouping of mosaic portraits in Rome of Popes who had deputed the building or rebuilding of the churches containing them show continuing figures holding models of the edifice, normally among a grouping of saints. Gradually these traditions worked their way downward the social scale, especially in illuminated manuscripts, where they are often owner portraits, equally the manuscripts were retained for use by the person commissioning them. For example, a chapel at Mals in S Tyrol has two fresco donor figures from before 881, one lay and the other of a tonsured cleric holding a model edifice.[12] In subsequent centuries bishops, abbots and other clergy were the donors most commonly shown, other than royalty, and they remained prominently represented in later periods.[13]

Donor portraits of noblemen and wealthy businessmen were becoming mutual in commissions past the 15th century, at the same fourth dimension as the panel portrait was beginning to be commissioned past this class - though at that place are possibly more donor portraits in larger works from churches surviving from before 1450 than panel portraits. A very common Netherlandish format from the mid-century was a pocket-sized diptych with a Madonna and Child, commonly on the left wing, and a "donor" on the right - the donor beingness here an possessor, as these were normally intended to exist kept in the subject's habitation. In these the portrait may adopt a praying pose,[14] or may pose more like the subject in a purely secular portrait.[15] The Wilton Diptych of Richard II of England was a precursor of these. In some of these diptychs the portrait of the original possessor has been over-painted with that of a afterwards one.[xvi]

A item convention in illuminated manuscripts was the "presentation portrait", where the manuscript began with a figure, often kneeling, presenting the manuscript to its owner, or sometimes the owner commissioning the book. The person presenting might be a courtier making a gift to his prince, but is often the author or the scribe, in which cases the recipient had really paid for the manuscript.[17]

Iconography of painted donor figures [edit]

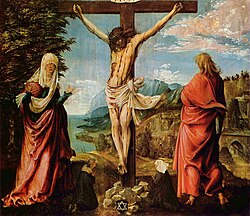

Crucifixion by Albrecht Altdorfer, c. 1514, with a tiny donor couple amongst the feet of the main figures. Altdorfer was one of the final major artists to retain this convention.

During the Centre Ages the donor figures oft were shown on a far smaller calibration than the sacred figures; a change dated past Dirk Kocks to the 14th century, though before examples in manuscripts can be found.[eighteen] A after convention was for figures at almost three-quarters of the size of the primary ones. From the 15th century Early Netherlandish painters like January van Eyck integrated, with varying degrees of subtlety, donor portraits into the space of the main scene of altarpieces, at the aforementioned scale as the main figures.

A comparable style tin exist found in Florentine painting from the aforementioned date, as in Masaccio'due south Holy Trinity (1425–28) in Santa Maria Novella where, however, the donors are shown kneeling on a sill exterior and beneath the principal architectural setting.[nineteen] This innovation, yet, did not appear in Venetian painting until the plow of the next century.[xx] Ordinarily the main figures ignore the presence of the interlopers in narrative scenes, although bystanding saints may put a supportive hand on the shoulder in a side-console. Simply in devotional subjects such equally a Madonna and Child, which were more probable to have been intended for the donor's home, the main figures may look at or bless the donor, as in the Memling shown.

Before the 15th century a physical likeness may not have often been attempted, or achieved; the individuals depicted may in whatever case often not have been available to the creative person, or even alive.[21] By the mid-15th century this was no longer the case, and donors of whom other likenesses survive can often be seen to be carefully portrayed, although, as in the Memling in a higher place, daughters in particular often appear as standardized beauties in the style of the day.[22]

In narrative scenes they began to be worked into the figures of the scene depicted, perhaps an innovation of Rogier van der Weyden, where they tin often be distinguished by their expensive contemporary dress. In Florence, where there was already a tradition of including portraits of city notables in crowd scenes (mentioned by Leon Battista Alberti), the Procession of the Magi by Benozzo Gozzoli (1459–61), which admittedly was in the individual chapel of the Palazzo Medici, is dominated past the glamorous procession containing more portraits of the Medici and their allies than tin can now be identified. By 1490, when the large Tornabuoni Chapel fresco wheel by Domenico Ghirlandaio was completed, family members and political allies of the Tornabuoni populate several scenes in considerable numbers, in addition to conventional kneeling portraits of Giovanni Tornabuoni and his wife.[24] In an ofttimes-quoted passage, John Pope-Hennessy caricatured 16th-century Italian donors:[25]

the vogue of the commonage portrait grew and grew ... condition and portraiture became inextricably entwined, and there was well-nigh nothing patrons would non do to intrude themselves in paintings; they would stone the women taken in infidelity, they would clean up after martyrdoms, they would serve at the table at Emmaus or in the Pharisee's house. The elders in the story of Suzannah were some of the few figures respectable Venetians were unwilling to impersonate. ... the simply contingency they did non envisage was what actually occurred, that their faces would survive only their names go astray.

In Italy donors, or owners, were rarely depicted as the major religious figures, but in the courts of Northern Europe in that location are several examples of this in the belatedly 15th and early 16th centuries, mostly in small panels not for public viewing.[8] [26] The almost notorious of these is the portrayal equally the Virgin lactans (or only mail service-lactans) of Agnès Sorel (died 1450), the mistress of Charles VII of France, in a panel by Jean Fouquet.[27]

Donor portraits in works for churches, and over-prominent heraldry, were disapproved of by clerical interpreters of the vague decrees on art of the Council of Trent, such as Saint Charles Borromeo,[28] but survived well into the Baroque menstruum, and developed a secular equivalent in history painting, although here it was often the main figures who were given the features of the commissioner. A very tardily example of the old Netherlandish format of the triptych with the donors on the fly panels is Rubens' Rockox Triptych of 1613–15, once in a church over the tombstone of the donors and now in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp. The key panel shows the Incredulity of Thomas ("Doubting Thomas") and the piece of work every bit a whole is cryptic as to whether the donors are represented equally occupying the same space every bit the sacred scene, with dissimilar indications in both directions.[29]

A farther secular development was the portrait historié, where groups of portrait sitters posed as historical or mythological figures. One of the almost famous and hitting groups of Bizarre donor portraits are those of the male members of the Cornaro family, who sit down in boxes as if at the theatre to either side of the sculpted altarpiece of Gian Lorenzo Bernini's Ecstasy of St Theresa (1652). These were derived from frescoes by Pellegrino Tibaldi a century early, which use the same conceit.[30]

Although donor portraits accept been relatively little studied as a singled-out genre, there has been more interest in contempo years, and a fence over their relationship, in Italy, to the rise of individualism with the Early Renaissance, and also over the changes in their iconography after the Black Decease of the mid-14th century.[31]

Gallery [edit]

-

Small donor with enthroned Madonna and Child, ca 1335

-

Giovanni di Paolo's Crucifixion with donor Jacopo di Bartolomeo, named in the inscription and with his coat of artillery at left

-

Hans Memling; the Madonna looks benevolently at the donor, who is presented by Saint Anthony the Swell, and blessed by the Christ-child

-

Geertgen tot Sint Jans, Raising of Lazarus, with five kneeling donor portraits (and peradventure the donor'southward dog). The very modest daughter was possibly an infant decease or a later addition to the family and the painting

-

-

-

A prosperous glassmaker and his family, 1596. The five children holding crosses had died; the two in black-trimmed white garments apparently before the painting was done, on the others the crosses were probably added after.[32]

Notes [edit]

- ^ Roberts, pp. i–3, 22

- ^ Run across particularly Roberts, 22–24 for a review of the historiography as to the motivations of donors

- ^ James WEALE, Généalogie de la famille Morales, in Le Beffroi, 1864–1865, pp 179–196.

- ^ Scheel, Johanna, Das altniederländische Stifterbild. Emotionsstrategien des Sehens und der Selbsterkenntnis, pp. 172–180, 241–249, Gebr. Isle of mann, Berlin, 2013

- ^ Scheel, Johanna, Das altniederländische Stifterbild. Emotionsstrategien des Sehens und der Selbsterkenntnis, pp. 317–318, Gebr. Mann, Berlin, 2013

- ^ Harbison, Craig, Jan van Eyck, The Play of Realism, pp.112, Reaktion Books, London, 1991, ISBN 0-948462-xviii-iii

- ^ In fact one-half of the 83 14th-century Venetian images, in what is intended to exist a complete catalogue by Roberts, are of this group type. Roberts, 32

- ^ a b Ainsworth, Maryan Westward. "Intentional Alterations of Early Netherlandish Painting". In Timeline of Fine art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. Accessed September 10, 2008

- ^ Roberts, 16–19. Quote on p. 19, note 63, from I Motti e facezie del Piovano Arlotto a pop 15th-century compilation of comic stories attributed to the real Piovano Arlotto, a priest of Pratolino well-nigh Florence.

- ^ Handbook, 67

- ^ Early Christian Chapels in the Westward: Decoration, Function and Patronage, pp. 97–99; Gillian Vallance Mackie, Gillian Mackie; University of Toronto Press, 2003, ISBN 0-8020-3504-3

- ^ Dodwell, 46

- ^ Roberts, 5–19 reviews the tradition

- ^ "example from NGA WAshington". Archived from the original on 2008-09-xviii. Retrieved 2008-09-x .

- ^ Example from NGA Washington Archived Oct eighteen, 2008, at the Wayback Motorcar

- ^ John Oliver Manus, Catherine Metzger, Ron Spronk; Prayers and Portraits: Unfolding the Netherlandish Diptych, true cat no 40, (National Gallery of Fine art (U.S.), Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten (Belgium)), Yale University Printing, 2006, ISBN 0-300-12155-5 - a diptych in the Fogg Museum Harvard

- ^ Burgundian frontispieces

- ^ King, 129. See further reading for Kocks.

- ^ Male monarch, 131

- ^ Penny, 110, discussing this. Archived 2017-01-16 at the Wayback Motorcar and another case by Marco Marziale

- ^ Memling seems to have replaced a generalized portrait of the wife of Sir John Donne with a more than personal one, mayhap later on Lady Donne travelled to Bruges, or a drawing was made in Calais for him. Run across the entry for the painting in National Gallery Catalogues: The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Paintings by Lorne Campbell, 1998, ISBN ane-85709-171-X, OL 392219M, OCLC 40732051, LCCN 98-66510, (also titled The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Schools)

- ^ The elder sons also seem very similar younger versions of their male parent's portrait

- ^ J.O. Manus & One thousand. Wolff, Early Netherlandish Painting, pp. 155–161, National Gallery of Art, Washington(catalogue)/Cambridge UP, 1986, ISBN 0-521-34016-0. The girls' mother may be in a Nativity in Birmingham, if it is indeed from the same altarpiece. Washington aspect the work to the "Main of the Prado Adoration of the Magi", but note that many attribute the girls alone to Rogier van der Weyden, the other'southward master.

- ^ Paola Tinagli, Women in Italian Renaissance Art: Gender, Representation, Identity, Manchester University Printing, pp. 64–72 1997, ISBN 0-7190-4054-Ten, discusses the donor portraits in the cycle in particular (especially the female person ones)

- ^ John Pope-Hennessy (meet Further reading), 22–23, quoted in Roberts, 27, notation 83. Judgement on Suzannah from M1 Berger & Berger, here

- ^ Campbell, 3–4, & 137

- ^ Campbell, iii–iv

- ^ Penny, 108

- ^ Jacobs, 311–312

- ^ Shearman, 182. The frescoes are in the Poggi Chapel, in San Giacomo Maggiore, Bologna.

- ^ Roberts, 20–24

- ^ Walter A. Friedrich: Die Wurzeln der nordböhmischen Glasindustrie und dice Glasmacherfamilie Friedrich (only bachelor in German), p. 233, Fuerth 2005, ISBN 3-00-015752-2

References [edit]

- Campbell, Lorne, Renaissance Portraits, European Portrait-Painting in the 14th, 15th and 16th Centuries, p. 151, 1990, Yale, ISBN 0-300-04675-8

- Dodwell, C.R.; The Pictorial arts of the West, 800–1200, 1993, Yale Up, ISBN 0-300-06493-four

- "Handbook". Art in the Christian World, 300–1500; A Handbook of Styles and Forms, by Yves Christe and others, Faber and Faber, 1982, ISBN 0-571-11941-vii

- Jacobs, Lynn F., "Rubens and the Northern Past: The Michielsen Triptych and the Thresholds of Modernity", The Art Bulletin, Vol. 91, No. 3 (September 2009), pp. 302–24, JSTOR 40645509

- King, Catherine. Renaissance Women Patrons, Manchester Academy Press, 1998, ISBN 0-7190-5289-0. Donor portraits are discussed on pp. 129–144

- Penny, Nicholas, National Gallery Catalogues (new series): The Sixteenth Century Italian Paintings, Volume I, 2004, National Gallery Publications Ltd, ISBN one-85709-908-7

- Roberts, Angela Marisol; Donor Portraits in Late Medieval Venice c.1280–1413, PhD thesis, 2007, Queens University, Canada (Large File)

- Johanna Scheel, Das altniederländische Stifterbild. Emotionsstrategien des Sehens und der Selbsterkenntnis, Gebr. Mann, Berlin, 2013, ISBN 978-3-7861-2695-9

- Shearman, John. Mannerism, 1967, Pelican, London, ISBN 0-14-020808-ix

Further reading [edit]

- Dirk Kocks, Die Stifterdarstellung in der italienischen Malerei des xiii.-fifteen. Jahrhunderts (The Donor Portrait in Italian Painting of the 13th to 15th centuries), Cologne, 1971

- John Pope-Hennessy; The Portrait in Renaissance Fine art, London, 1966

- Johanna Scheel, Das altniederländische Stifterbild. Emotionsstrategien des Sehens und der Selbsterkenntnis, Berlin, 2013

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donor_portrait